Lua modules

Lua modules allow you to structure your project and create reusable library code. It is generally a good idea to avoid duplication in your projects. Defold allows you to use Lua’s module functionality to include script files into other script files. This allows you to encapsulate functionality (and data) in an external script file for reuse in game object and GUI script files.

Requiring Lua files

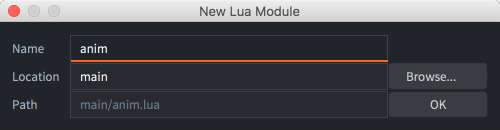

Lua code stored in files with file ending “.lua” somewhere in your game project structure can be required into script and gui script files. To create a new Lua module file, right click the folder you want to create it in in the Assets view, then select New... ▸ Lua Module. Give the file a unique name and press Ok:

Suppose the following code is added to the file “main/anim.lua”:

function direction_animation(direction, char)

local d = ""

if direction.x > 0 then

d = "right"

elseif direction.x < 0 then

d = "left"

elseif direction.y > 0 then

d = "up"

elseif direction.y < 0 then

d = "down"

end

return hash(char .. "-" .. d)

end

Then it’s possible for any script to require this file and use the function:

require "main.anim"

function update(self, dt)

-- update position, set direction etc

...

-- set animation

local anim = direction_animation(self.dir, "player")

if anim ~= self.current_anim then

msg.post("#sprite", "play_animation", { id = anim })

self.current_anim = anim

end

end

The function require loads the given module. It starts by looking into the package.loaded table to determine whether the module is already loaded. If it is, then require returns the value stored at package.loaded[module_name]. Otherwise, it loads and evaluates the file via a loader.

The syntax of the filename string provided to require is a bit special. Lua replaces ‘.’ characters in the filename string with path separators: ‘/’ on macOS and Linux and ‘\’ on Windows.

Note that it is usually a bad idea to use the global scope to store state and define functions like we did above. You risk naming collisions, exposing the state of the module or introduce coupling between users of the module.

Modules

To encapsulate data and functions, Lua uses modules. A Lua module is a regular Lua table that is used to contain functions and data. The table is declared local not to pollute the global scope:

local M = {}

-- private

local message = "Hello world!"

function M.hello()

print(message)

end

return M

The module can then be used. Again, it is preferred to assign it to a local variable:

local m = require "mymodule"

m.hello() --> "Hello world!"

Hot reloading modules

Consider a simple module:

-- module.lua

local M = {} -- creates a new table in the local scope

M.value = 4711

return M

And a user of the module:

local m = require "module"

print(m.value) --> "4711" (even if "module.lua" is changed and hot reloaded)

If you hot reload the module file the code is run again, but nothing happens with m.value. Why is that?

First, the table created in “module.lua” is created in local scope and a reference to that table is returned to the user. Reloading “module.lua” evaluates the module code again but that creates a new table in the local scope instead of updating the table m refers to.

Secondly, Lua caches required files. The first time a file is required, it is put in the table package.loaded so it can be read faster on subsequent requires. You can force a file to be re-read from disk by setting the file’s entry to nil: package.loaded["my_module"] = nil.

To properly hot reload a module, you need to reload the module, reset the cache and then reload all files that uses the module. This is far from optimal.

Instead, you might consider a workaround to use during development: put the module table in the global scope and have M refer to the global table instead of creating a new table each time the file evaluates. Reloading the module then changes the contents of the global table:

--- module.lua

-- Replace with local M = {} when done

uniquevariable12345 = uniquevariable12345 or {}

local M = uniquevariable12345

M.value = 4711

return M

Modules and state

Stateful modules keep an internal state that is shared between all users of the module and can be compared to singletons:

local M = {}

-- all users of the module will share this table

local state = {}

function M.do_something(foobar)

table.insert(state, foobar)

end

return M

A stateless module on the other hand doesn’t keep any internal state. Instead it provides a mechanism to externalize the state into a separate table that is local to the module user. Here are a few different ways to implement this:

- Using a state table

- Perhaps the easiest approach is to use a constructor function that returns a new table containing only state. The state is explicitly passed to the module as the first parameter of every function that manipulates the state table.

local M = {} function M.alter_state(the_state, v) the_state.value = the_state.value + v end function M.get_state(the_state) return the_state.value end function M.new(v) local state = { value = v } return state end return MUse the module like this:

local m = require "main.mymodule" local my_state = m.new(42) m.alter_state(my_state, 1) print(m.get_state(my_state)) --> 43 - Using metatables

- Another approach is to use a constructor function that returns a new table with state and the public functions of the module each time it’s called:

local M = {} function M:alter_state(v) -- self is added as first argument when using : notation self.value = self.value + v end function M:get_state() return self.value end function M.new(v) local state = { value = v } return setmetatable(state, { __index = M }) end return MUse the module like this:

local m = require "main.mymodule" local my_state = m.new(42) my_state:alter_state(1) -- "my_state" is added as first argument when using : notation print(my_state:get_state()) --> 43 - Using closures

- A third way is to return a closure containing all state and functions. There is no need to pass the instance as an argument (either explicitly or implicitly using the colon operator) like when using metatables. This method is also somewhat faster than using metatables since function calls does not need to go through the

__indexmetamethods but each closure contains its own copy of the methods so memory consumption is higher.

local M = {}

function M.new(v)

local state = {

value = v

}

state.alter_state = function(v)

state.value = state.value + v

end

state.get_state = function()

return state.value

end

return state

end

return M

Use the module like this:

local m = require "main.mymodule"

local my_state = m.new(42)

my_state.alter_state(1)

print(my_state.get_state())

- English

- 中文 (Chinese)

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Νεοελληνική γλώσσα (Greek)

- Język polski (Polish)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Русский (Russian)

- Українська (Ukranian)

Did you spot an error or do you have a suggestion? Please let us know on GitHub!

GITHUB